The Digital "Sankarification" of Captain Ibrahim Traore

"come, let us make (the) man in our own image"

Introduction

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, is officially English-speaking and renowned for its deeply fragmented and often corrupt political climate. In this environment, many Nigerians remain largely unaware of developments in neighboring African countries. Most would struggle to name Ghana’s political parties or identify Cameroon’s current president. This is not solely due to pride, self-absorption or indifference. Rather, it reflects a population of over 200 million people intensely preoccupied with its own social, economical, political, and cultural challenges, alongside the overwhelming influence of some global cultural trends.

At the same time, external cultural forces have profoundly shaped the Nigerian psyche. In the 1990s and 2000s, American hip-hop and Indian cinema (Bollywood) dominated youth culture, providing templates for music, fashion, and even local film industries. Today, Korean pop music (K-pop) and dramas are captivating a new generation, with Nigerian Gen Zs forming vibrant fan communities and even integrating Korean language and aesthetics into their daily lives. These global influences often overshadow regional African affairs, reinforcing a worldview oriented more toward the West and Asia than toward neighboring countries.

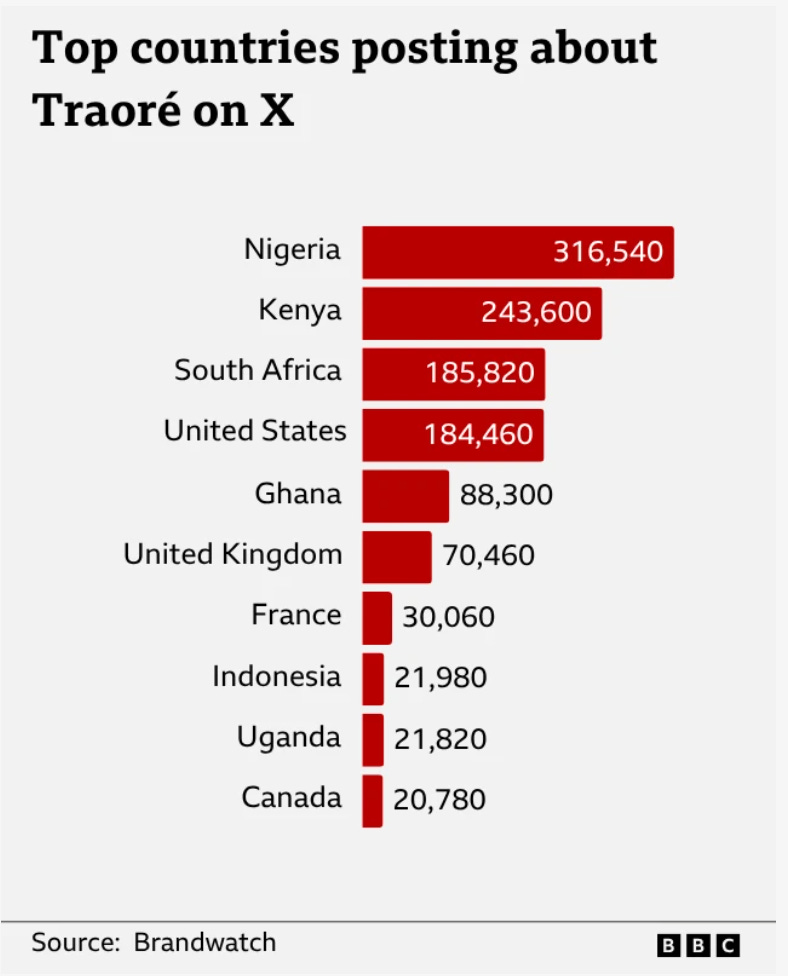

So, while the average Nigerian may not be able to recognize the president of Gabon in a crowd or accurately recall the capital of Angola, over the past year, many of them have become very familiar with images and videos of a young, charismatic military leader in camouflage. At first, these posts (circulating on Facebook, Twitter/X, Instagram and TikTok) largely went unnoticed. But continuous reinforcement through repeated exposure has made Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso a known figure. He is frequently depicted as a transformative leader who has rescued his country from the “evil hands” of Western (a.k.a French) domination, with posts touting new industries and sweeping reforms, especially from “pan-Africanist” social-media accounts. Interestingly, some recipients of this well-oiled spin are even unaware that Burkina Faso is a francophone country or that Traoré himself does not speak English. Yet, stories (in English, generated with artificial intelligence) about free education, new housing, and booming tomato paste factories abound—few of them true, many exaggerated and others, entirely fabricated.

How did our average Nigerian, who is often disconnected from regional geopolitics, suddenly become so well-versed in the affairs of Burkina Faso? The answer lies in the digital “Sankarification” of Ibrahim Traoré.

Through social media, Traoré has been reborn, reframed, and propagandized as the second coming of Thomas Sankara (a mostly well-regarded revolutionary icon whose legacy still resonates across francophone Africa and the diaspora). In this article, I will explore how this digital mythmaking (largely driven by Russian disinformation networks) has elevated Traoré’s image and what it reveals about the power of online narratives in shaping modern African consciousness.

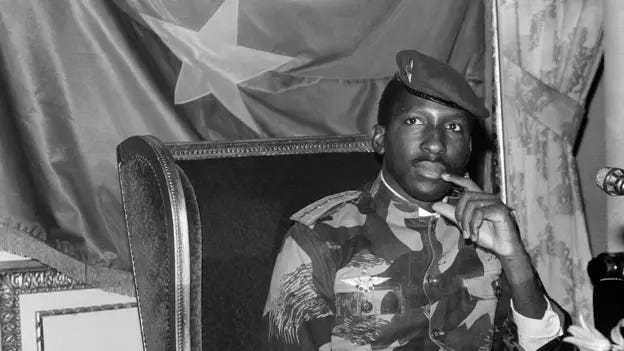

The Man, Thomas Isidore Sankara

To understand Thomas Sankara’s relevance to our story, we need to travel back about forty years. Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara was a young, charismatic military officer who rose to power in Burkina Faso (then called Upper or Haute Volta) through a coup in 1983. It was a time when African countries were still dealing with “teething” issues associated with democracy and when such military takeovers were more common1. At just 34, Sankara became president and immediately set about transforming the country into an anti-capitalist and anti-imperial “utopia”. He renamed it Burkina Faso, meaning “land of upright or honorable people,” to mark a new national identity free from its colonial past.

Years before he became the leader of the Burkinabès, Sankara’s worldview was shaped by his military training in Madagascar, it was there that be became exposed to Marxist and pan-Africanist idea(l)s. Unlike other copycats and grifters in the “revolution” world, Thomas Sankara was a genuine ideologue: he lived modestly, famously riding a bicycle to work, he also sent his kids to public schools. Before becoming president, he served as Minister of Information and later became Prime Minister, where his outspoken and radical views led to his imprisonment by the government he served. His close ally, Blaise Compaoré, led a coup that freed Sankara and installed him as leader (a decision Compaoré would later work to reverse).

As president, Sankara launched a radical program of reforms. He targeted the base of the Maslow’s pyramid and prioritized basic needs in Burkina Faso (food, housing, healthcare, and education), he implemented mass vaccination campaigns, and a nationwide literacy drive. He promoted women’s rights, outlawed forced marriages, and banned female circumcision. He rejected luxury, selling off government limousines and making the cheapest car in the country (at the time, Renault-5s) the official vehicle for himself and his ministers. Ernest Harsch describes him as “an idealist, demanding, and rigorous”.

However, his leadership was not without controversy. Sankara’s government executed some officials from the previous regime and detained political opponents that disagreed with him. Still, he remained immensely popular with ordinary Burkinabè for what they perceived as his integrity, vision, and insistence on self-reliance. While some of Sankara’s socialist policies were successful at first, the gains proved difficult to sustain. By 1987, Burkina Faso had become heavily dependent again on foreign remittances, aid and trade (most especially, with Ivory Coast), accompanied with a heavy national debt burden that continued to balloon.

Sankara’s life was dramatically cut short in 1987 when he was assassinated in a coup led by his former friend (and minister of justice), Compaoré, who ended up ruling Burkina Faso for 27 years until 2014, and reversed most of the economic and geopolitical policies Sankara had attempted to enact. Despite his brief time in power, Sankara’s legacy as a revolutionary, anti-imperialist, and advocate for African self-determination endures, even more among leftists and communists in Europe and the Americas with a clout similar to that of Che Guevara.

Sankara’s relevance to this story lies in how his image and ideals have been revived and reframed in the figure of Ibrahim Traoré. Traoré’s rhetoric, policies, and even his personal style are being deliberately postured to echo Sankara’s, fueling a digital and popular movement that casts him as the modern heir to Sankara’s revolutionary vision.

The Sankarification of Ibrahim Traoré—Who Pays the Piper? Who Plays the Tune?

To remake a man (or more precisely, to create the image of a man in the similitude of another man) what tools are required? In today’s world, the answer always starts with money, but that’s only a part of it. Traoré’s new public persona has relied heavily on a combination of sophisticated propaganda, social media virality, and back-end geopolitical maneuvering.

The image to be re-made must echo the legitimacy of a revered figure, be broadcast to a population susceptible to propaganda, and often emerge in a context of widespread dissatisfaction. Add to this the geopolitical ambitions of a declining superpower seeking renewed influence, especially in regions like Africa, then you have the complete recipe that has catalyzed the emergence of Ibrahim Traore as the second coming of Thomas Isidore Sankara.

On September 30, 2022, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, flanked by armed soldiers in camouflage and masks, announced the suspension of Burkina Faso’s constitution and the ouster of President Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba. This marked the country’s second coup that year. Earlier, Traoré had assisted Damiba in toppling the democratically elected president, Roch Marc Kaboré. This context is particularly important: it helps explain Traoré’s current paranoia (including rumours of “assassination attempts” on him) about being overthrown by his own allies—an environment where, as the saying goes, “there is no honour among putschists.”

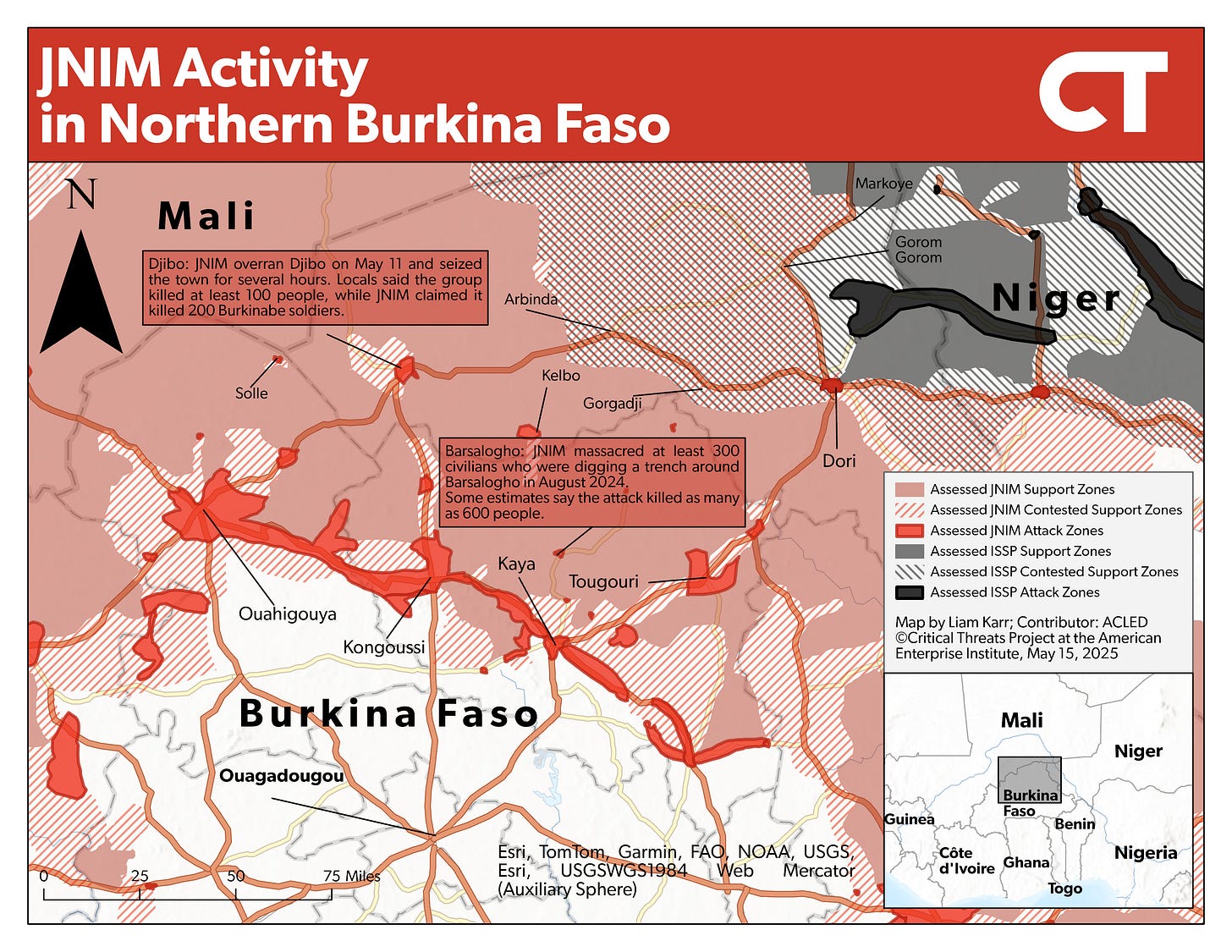

Traoré capitalized on widespread frustration with Damiba’s failure to contain the JNIM-led jihadist insurgency, which continues to wreak havoc across Burkina Faso. Remarkably, Traoré was just 34 when he seized power, the same age as Thomas Sankara (a comparison that fueled his initial popularity especially since previous coup leaders were older). Described as quiet and academically gifted, Traoré graduated with honors in geology from the University of Ouagadougou. He joined the Burkina Faso military in 2009, and within 13 years, rose to lead both the country and its armed forces.

After the coup, Traoré criticized Damiba’s administration for its failures in security and economic management, promising to restore Burkina Faso’s former glory and to hold democratic elections by July 2024. Predictably, these elections have not taken place, and there is little indication that they will happen anytime soon.

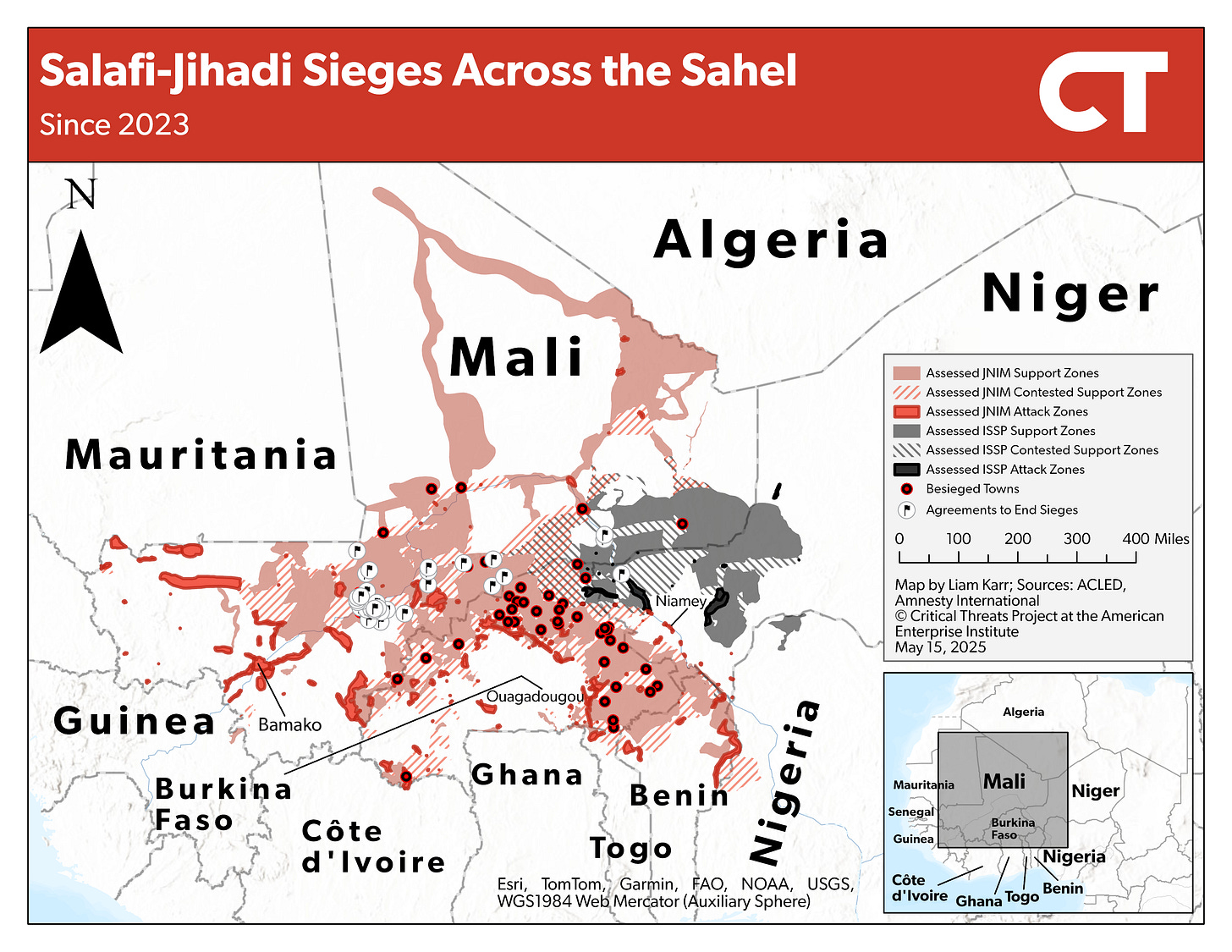

Traoré’s rise and the propaganda surrounding him serve a dual purpose. First, his youth, charisma, and the symbolic connection to Sankara allow him to posture as a legitimate pan-Africanist leader who rejects Western influence and aspires to liberate his people from “neo-colonial” control. This narrative, fuelled by Russian online troll farms in the Sahel, greatly aligns with Russia’s strategic interests in Africa, as Moscow seeks to (counter Western sway and) expand its influence amid setbacks in Syria and Ukraine. Russia’s support, including military instructors and security assistance, has helped Traoré consolidate power, while anti-Western rhetoric resonates with many young Africans who have rightly become disillusioned by their own governments.

Secondly, domestically, Traoré’s record is faltering, and the propaganda serves as a needed distraction. State security has deteriorated further, with JNIM making significant territorial gains, including the recent seizure of a provincial capital. To manage negative publicity, Traoré has cracked down on dissent, banning and expelling all independent media, a stark contrast to Sankara’s relative openness with the media.

The Burkina Faso economy remains heavily dependent on gold exports. While the government has announced the nationalization of gold mines and new policies to keep more wealth in-country, the sector’s challenges persist, and Burkina Faso continues to rely on international aid and loans, including from the IMF with over $128 million disbursed or pending as of mid-2025 (despite anti-IMF rhetoric regularly spouted by Traoré and his network of online “pan-Africanists”).

In very plain terms, the current image of Traoré as a revolutionary savior is largely a mirage, carefully crafted for both domestic and international audiences. The reality is far more complex: Burkina Faso remains deeply unstable, and its supposed break from Western influence has not (at the time of writing) translated into improved security or prosperity. The digital sankarification of Traoré as the answer to all its travails is simply fugazi—it drifts, it floats, and it disappears.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Well, I wrote this because I grew up in the shadow of the Abacha military government and I have seen firsthand the dangers of authoritarian rule. The current propaganda surrounding Ibrahim Traoré in Burkina Faso is not just a regional phenomenon, it is a psychological campaign aimed at normalizing coups, dictatorships, and the suppression of dissent across West Africa. If left unchecked, this trend threatens to undo the hard-won democratic gains in more African countries, all in the service of Russia’s geopolitical interests.

Yes, the Nigerian democracy is flawed—maybe even all of Africa’s democracies are. I, myself, have become deeply disillusioned with our “democratic” leaders and the harm they have done to our country. But I would still choose this imperfect system over a return to military rule, where citizens are made subservient, the media is silenced, and our freedoms are erased. That is why I wrote this. Because it truly frightens me to see how effective the Traoré psy-op has become, and how many young Nigerians (unaware of the true situation in Burkina Faso) are now receptive to the idea of military leadership.

So, where do we go from here? The answer lies in confronting this wave of disinformation and psychological manipulation head-on. Civil society, the media, and educational institutions must work together to raise awareness, and promote critical thinking among young people (and maybe even old people).

Governments and intelligence agencies need to take information warfare seriously and invest in strategies to counter false narratives and strengthen democratic norms. Most importantly, we must not allow our justified frustrations with democracy’s failures to blind us to the far greater dangers of authoritarianism.

I rest my case.

(“The Legacies of Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary Experience in Retrospect,” 2013)

Really good research and writing

Thank you for reminding me that im not immune to propaganda.