The “Alabuga Start” Story

State-Sanctioned Exploitation and Modern Slavery in Africa

Introduction

In the early hours of Friday, May 30, Nigerian-born, UK-based accountant and writer Feyi Fawenhimi (@DoubleEph) posted a tweet that caught my attention. He shared four images: the first three were screenshots from a story in The Economist detailing the exploitation of young Africans in Russia, while the fourth was a public release from Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Education. This official statement confirmed (and implicated Nigeria in) the broader concerns raised by the Economist article. My reaction wasn’t one of shock or sadness, but rather a familiar sense of resignation and disappointment that has come to define my life as a Nigerian.

To the casual observer, the ministry’s release appeared to be a routine advertisement for a scholarship at Alabuga Polytech in Tatarstan, Russia. [Such opportunities have long been part of Nigeria’s positive relationship with Russia. Before the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, hundreds of Nigerian students pursued degrees in medicine, engineering, and other STEM fields at Russian and Ukrainian universities. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed this dynamic. Stricter travel restrictions, heightened safety concerns, and diplomatic tensions have made studying in Russia and Ukraine increasingly difficult, forcing many Nigerians to reconsider their options.]

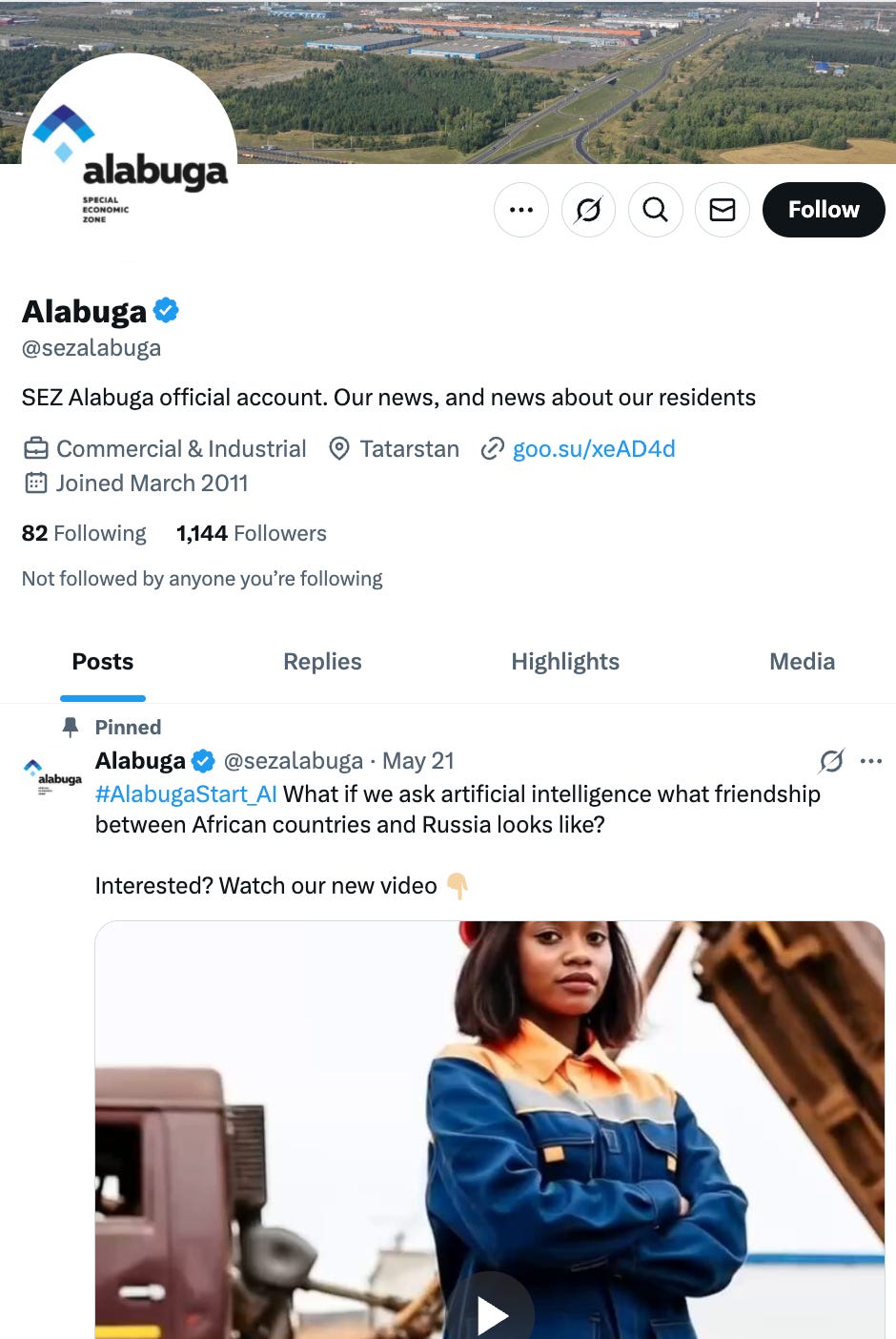

Alabuga is a special economic zone (SEZ) of industrial and production type, located in the Yelabuzhsky District of the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia. The management company of SEZ Alabuga is wholly owned by the Russian Federation through the Joint Stock Company "Special Economic Zones," with the Ministry of Land and Property of the Republic of Tatarstan serving as its sole shareholder.

On the surface, the Alabuga scholarship seemed like a valuable chance for students to study fields such as industrial robotics, automation, and electrical installation—courses that are either unavailable in Nigeria or underfunded if they are. But the advertisement omitted crucial details. It failed to mention that the program specifically targeted girls aged 18–22 for a reason and that these young women would be assembling Shahed drone parts (imported from Iran), in Russian factories that may become legitimate military targets for Ukrainian strikes. This raises some interesting questions: Why would Russia (the world’s ninth most populous country) need to recruit young African women for such work? Why was the full scope of the program concealed from both the recruits and the public? Why is the Nigerian government (and other African governments) endorsing the exploitation and debasement of their own people?

Well, it appears that Russia, facing labor shortages and seeking a workforce that is “dispensable, pays attention to detail, exploitable, and pliable,” has devised an elaborate scheme which involves collaborating with African governments and exploiting local poverty, to lure hundreds of unsuspecting young women into what may be the last jobs they ever hold.

This exploitation has unfolded in plain sight, yet has gone largely unnoticed. This article seeks to assemble a clear picture and highlight the grave risks facing young Africans girls caught in this new, state-sanctioned form of exploitation.

How Did We Get Here?

While not the main focus of this article, it is important to provide some background on how we arrived at the current situation. After World War II, Russia (as the USSR) emerged as a superpower. Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has sought to restore its former geographic and military influence, often by targeting neighboring states it perceives as vulnerable.

The formula is simple: Military incursions followed by ceasefires that result in territorial losses for the targeted country and temporary peace until the next conflict.

This approach was first seen in the 2008 war with Georgia, where Russia intervened under the pretext of defending separatist regions, ultimately occupying territory and imposing a ceasefire on unfavorable terms for Georgia. The strategy continued in Ukraine, beginning with the annexation of Crimea and support for separatists in eastern Ukraine in 2014, escalating to a full-scale invasion in 2022.

Despite repeated denials from the Russian government on the possibility of a war or invasion, the 2022 invasion of Ukraine was eventually launched as a so-called “special military operation.” Putin’s stated objective was a swift campaign to seize Kyiv, remove President Zelensky, and install a pro-Russian government, effectively turning Ukraine into a vassal state. However, as we all know in 2025, it is clear that this plan has not succeeded. The Russian military, once regarded as the world’s second most powerful, has been hampered by corruption, complacency, and unexpectedly strong Ukrainian resistance, which has been majorly supported by Western weaponry. The conflict has become a protracted war of attrition, with no clear end in sight.

As the war dragged on, Western sanctions severely restricted Russia’s access to advanced weaponry and critical components, prompting Moscow to seek assistance from allies such as Iran, China, and North Korea. While China’s support has largely remained covert due to concerns about secondary sanctions, Iran and North Korea (already heavily sanctioned, with nothing else to lose) have continued to supply Russia with crucial military technology.

Iran’s Shahed drones, in particular, have become central to Russia’s campaign. These drones are inexpensive, can be produced rapidly, and are highly effective in striking Ukrainian targets. Iran provided Russia with both the technology and raw materials for these drones, leading to the establishment of assembly and production sites within Russia. The Alabuga Special Economic Zone has become a primary hub for assembling and manufacturing Shahed drones, leveraging imported components and technical assistance from Iran.

A Campaign Of Deceit

Just as I outlined in my previous article, “The Digital Sankarification of Ibrahim Traore,” Russia has long mastered the art of information warfare. The same toolkit: influencers, media, and policy levers, was deployed to recruit these young, unsuspecting African girls for its latest strategy in Alabuga.

Russia’s campaign of deceit has unfolded in two critical phases, with African governments (who should be safeguarding their vulnerable citizens) serving more as enablers than protectors.

Firstly, Russia established a veneer of legitimacy by announcing, through state policy, that the Alabuga Special Economic Zone (and by extension, Alabuga Polytech) had a newfound interest in training young African women in technology fields supposedly inaccessible in their home countries.

Once this narrative was in place, Russian officials reached out via diplomatic channels to governments such as Nigeria, Somalia, Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique and Ghana, presenting a scholarship opportunity tailored to their young, female demographic. Personally, I find quite astonishing that, in the midst of a war, a Russian government educational policy specifically targeting 18- to 22-year-old women did not trigger alarm bells among the leadership of these countries.

Secondly, Russia launched an extensive news media and social media campaign. In Nigeria, for example, the Federal Ministry of Education publicized the offer of 150 scholarships, while various media outlets (some unwitting, others with a pro-Russia slant) amplified the message.

This formula was repeated in several of the target countries. For example, in Somalia, where a government minister visited the Alabuga zone for a photo-op with the recruits, and in Kampala, where tech competitions were promoted as a pathway to Alabuga scholarships.

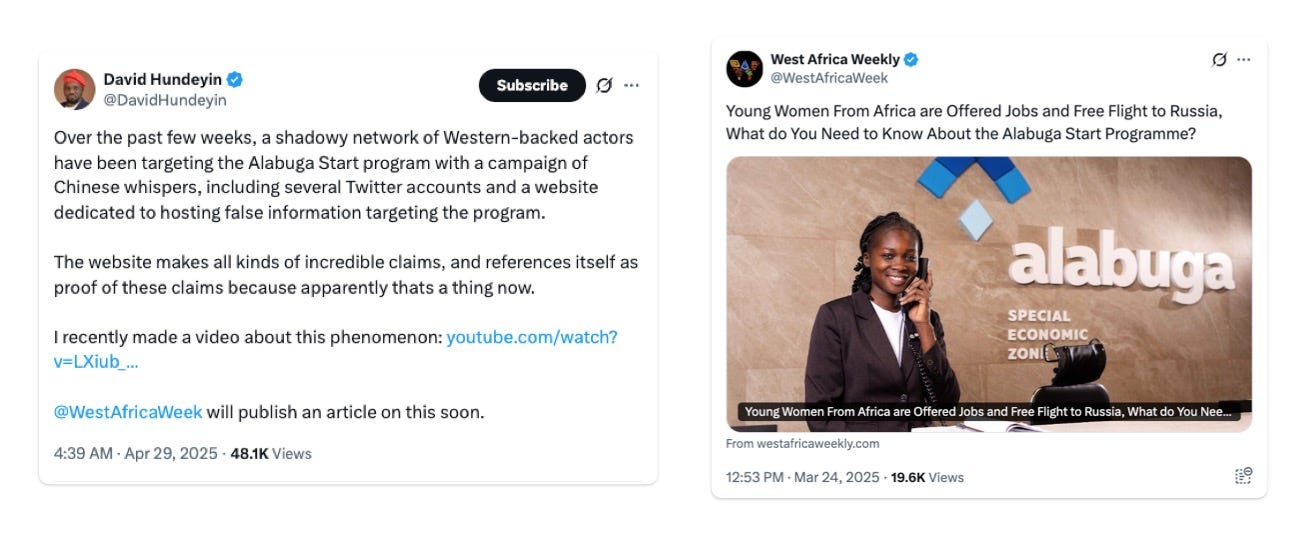

A prominent figure in the Nigerian media landscape, “journalist” David Hundeyin, was also a key promoter of these clandestine efforts to recruit young Nigerian girls to Russia’s Alabuga drone factories.

Hundeyin, through his personal social media accounts (Twitter/X, Youtube) and his media outlet, West Africa Weekly, published several content defending the “Alabuga Start” program and dismissing critical reports (even from other Nigerians) as “Western disinformation campaigns”. In an article published on April 30, 2025, Hundeyin argued that allegations of exploitation and trafficking were part of an information war against Russia, and he questioned the credibility of sources reporting abuses in Alabuga.

TikTok, Facebook, and Telegram were also used to target these young women with promises of opportunity and adventure. Influencers and polished videos painted a picture of empowerment and career advancement, omitting the more painful reality. We now know from several first-hand reports that these women faced risk of death from Ukrainian attacks, long hours, surveillance, lower-than-promised wages, and hazardous working environments, with little recourse or ability to leave (a.k.a: slavery).

This campaign and lesson in modern slavery has exploited the lax oversight and complacency of African governments, as well as the absence of effective safeguards in their policies, to funnel young women into Russia’s wartime labor machine. The result is a stark example of modern exploitation masquerading as opportunity: A campaign of deceit that demands urgent scrutiny and accountability.

Where Do We Go From Here?

As I described in the introduction of “JAMB, A Cultural Lack of Accountability and the Anatomy of Educational Policy Failure in Nigeria,” I, like many other Nigerians, have come to expect absolutely nothing from our own government. In the Nigerian dream, the social contract is nonexistent. Yet, even in my state of perpetual resignation and lack of expectations, my government still manages to disappoint me.

The federal government of Nigeria has denied any involvement in the Alabuga “modern slavery” scheme. While I believe that it’s unlikely that the government acted out of malice, our country seems trapped in a cycle of incompetence that continually harms its most vulnerable citizens—sometimes with tragic consequences, as seen in this “Alabuga Start” story.

In so many ways, incompetence may end up being more consequential and harmful than malice.

I rest my case.